“We are people of this time and this place. The ningher canoe project was never simply about making a canoe. It has always been about journeys. Journeys of acknowledging deep and profound loss. Journeys about recovery, relationships, healing and struggling to regain control. Of what it takes to make a journey in the hope of becoming whole once more.

Tasmanian Aboriginal people are honoured to feel the love of the broader community as we have undertaken this poignant and important cultural step in recovering our precious culture. There is no failure. A journey is a journey, regardless of its outcome. I see you all here with us on this journey, and I know that this small step we have taken has been successful beyond our wildest dreams, as you are here with us, believing in our commitment to our culture, to this place, and the possibility that we can do important things together.

We built and launched a ningher, a canoe, and for a short time it graced the waters of the Derwent River. For a short time, you saw the passion in our hearts for practicing our culture: right here, right now.

Although the canoe could not make the full journey here today, it still stands as a powerful achievement for all of us. For my people, it is a step forward, and although the journey may be painful, full of risk and expectation not realised at times, it is also a journey of hope, beauty, strength, healing and spirit. The journey is ours, and we are proud to have honestly shared it with you. What this journey has meant to others is not for us to say, but we are listening.

We give you our humble thanks in travelling with us during ningher canoe, and we invite you to keep travelling with us, as MONA and Dark MOFO have, to take small steps together, honestly, and in the spirit of becoming whole once more.

Living Culture.”

Cultural Producer Fiona Hamilton’s opening address at Waterman’s Dock, Hobart.

Dry lightning strike. Image by Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

Mannalargenna said that the two men in the sky first gave the natives fire, that they stood all around. Woorady said Parpeder gave fire to the Brune natives. Journal of G. A. Robinson, 28 December, 1831

*******

“If they only had fire,” said Prometheus to himself, “they could at least warm themselves and cook their food; and after a while they could learn to make tools and build themselves houses. Without fire, they are worse off than the beasts. ”Then he went boldly to Jupiter and begged him to give fire to men, that so they might have a little comfort through the long, dreary months of winter. “Not a spark will I give,” said Jupiter. “No, indeed! Why, if men had fire they might become strong and wise like ourselves, and after a while they would drive us out of our kingdom. From ‘The Story of Prometheus‘, James Baldwin, 1923

There are a great many myths about Tasmanian Aboriginal people. It is strange that the most widespread of these myths – that we are gone – still persists in the minds of Australians, when so much of our continuing culture can be seen by those who care to look.

Another myth is still hotly debated by anthropologists, historians and others who try to tell our story. Many scientists such as Rhys Jones, Jared Diamond and Tim Flannery asserted or repeated the myth that Tasmanian Aboriginal people did not know how to make fire. More scholarly research easily sweeps away their suppositions. But scientific hear-say is not the most bizarre use of such ignorance. Creationists have used this as evidence of the Great Biblical Flood, marking us as degenerate; while campaigners against Aboriginal Rights have disparaged the richness of Aboriginal culture to argue that our ancestors should not have been accorded even the most basic of human rights in the face of invasion and dispossession. Keith Windschuttle used this myth to suggest that we were more primitive than Neanderthals!

Aboriginal fire-making in Tasmania had been recorded as early as 1773 by several French and British explorers. A range of techniques were used to make fire – to keep fire burning – and to transport fire while walking or travelling in canoes. But fire is not just an elemental force in Tasmanian Aboriginal culture. It carries powerful stories.

The ningher canoe will bring fire to Dark Mofo in 2014 in the same way that Prometheus brought fire from Olympus to give to mortal men in the stories of Greek mythology. These legends are older than history. And they are stories that unite human culture with a deep shared history. Like the tale of Prometheus, traditional Tasmanian stories tell of powerful gods from the sky who brought fire to our world. Our stories are no different than those at the foundation of Western civilisation. In fact, Tasmanian stories are older than the Greek versions by tens of thousands of years.

When Europeans first began to occupy Tasmania, their ignorance of fire was soon clear. The native grasslands of the Midlands looked like a perfect run for sheep. They did not realise that this was pasture created by the use of fire. Our ancestors had ‘farmed’ kangaroo for a thousand generations – burning the old grass to generate fresh growth, and to keep the scrub from overgrowing the vegetation most enjoyed by mobs of kangaroo that would be regularly harvested for meat and fur.

Today fire is feared in Tasmania. No longer a tool, it is a threatening reminder that modern ways of living on our island are not in accord with the life of the landscape. Authorities try to banish fire from ecosystems that have grown up with burning as an everyday part of life since our ancestors arrived here over forty thousand years ago.

Fire Danger. Image courtesy of Greg Lehman

The ningher canoe will bring together the elemental and cultural forces of Tasmania. Bark and reeds grown from earth will be borne on the waters of the Derwent River to become a ceremonial fire for the City of Hobart. The Canoe-makers have crafted a canoe and tended a fire to dry, shape and warm. They will bring embers to be fueled by winter winds into a great Solstice fire at Salamanca Place. This fire will blaze for the Dark Mofo festival and for all those who join the celebration – in the hope that ignorance of Tasmania’s deep culture will be burned away – that we will be united in our shared stories – and most importantly, that our ways of living on this island will no longer be fueled by ignorance and greed. The spirit of wisdom and sharing; call it Prometheus or Parpeder, will be there – as part of the ningher story.

ningher fire drying reeds for canoe-making. Image courtesy of Fi Hamilton.

Brendon (Buck) Brown tends the fire that is an intrinsic part of the ceremony of canoe-making. Image courtesy Fiona Hamilton

When Francois Péron published the first detailed European account of a Tasmanian canoe in 1807, he described a vessel just like the one now taking shape at MONA. On the morning of arriving with Capt. Nicholas Baudin in the corvette Géographe, Péron was making his way overland to Port Cygnet in search of a watering place for his ships when he stumbled on two canoes laid up on the shore. Made of three rolls of bark, bound together with string, each was equipped with a clay hearth containing a smouldering fire.

The Frenchmen had no clue to the identity of the makers of these canoes. It probably did not even occur to them that this might be important.

Yet only a few hours before, Péron had his first meeting with a young Tasmanian Aboriginal man. He wrote in his journal:

(13 January, 1803)

‘…our chaloupe (ships boat) seemed to attract his attention still more than our persons, and after examining us some minutes, he jumped into the boat: there, without troubling himself with, or even noticing the seamen who were in her, he seemed quite absorbed in his new subject. The thickness of the ribs and planks, the strength of the construction, the rudder, the oars, the masts, the sails, he observed in silence, and with great attention, and with the most unequivocal signs of interest and reflection …he made several attempts to push off the chaloupe, but the small hawser which fastened it, made his efforts of no avail, he was therefore obliged to give up the attempt and to return to us, after giving us the most striking demonstrations of attention and reflection.’

Who would take so much detailed interest in the construction of the french chaloupe, except a boat builder? Péron did not realise it, but he had probably just met his first Tasmanian Canoe Master – who was clearly keen to give this strange boat a sea-trial! Sadly, Péron did not find out this man’s name.

A sketch of the canoe found by Peron. Image courtesy of the Museum of Natural History, Le Havre.

It took until 1829 for another European, George Augustus Robinson, to finally record the name of a Tasmanian Canoe Master. Robinson describes him as possessing ‘…a first rate characteristical skill in nautical affairs and is esteemed a superior navigator. He has occasionally made comparatively long voyages extending a long way up the Huon River and is a perfect adept in constructing catamarans.’ This man, Mangerner, was the father of Trucanini. A countryman of Mangerner’s, and the husband of Trucanini, was also an expert canoemaker. His name was Woorrady.

Woorrady. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Woorrady is known to have made dozens of canoes, using paperbark, stringybark and rushes. He told Robinson of the great seafaring nations of southern Tasmania:

‘Tonight WOORRADY entertained us with a relation of the exploits of his nation and neighbouring nations or allies. Said that the NEEDWONNE natives-as also the Brune, PANGHEININGH and TIMEQUONE -went off in catamarans to the De Witt Island and to the different rocks, and speared seal and brought them to the mainland. Also went to the Eddystone and speared seal: this rock is miles distant and is a dangerous enterprise. Many hundred natives have been lost on those occasions. Those nations to the southward of the island was a maritime people. Their catamarans was large, the size of a whaleboat, carrying seven or eight people, their dogs and spears.‘

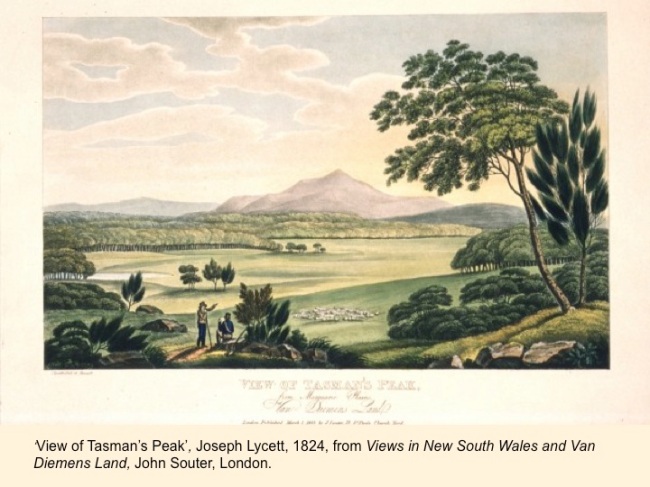

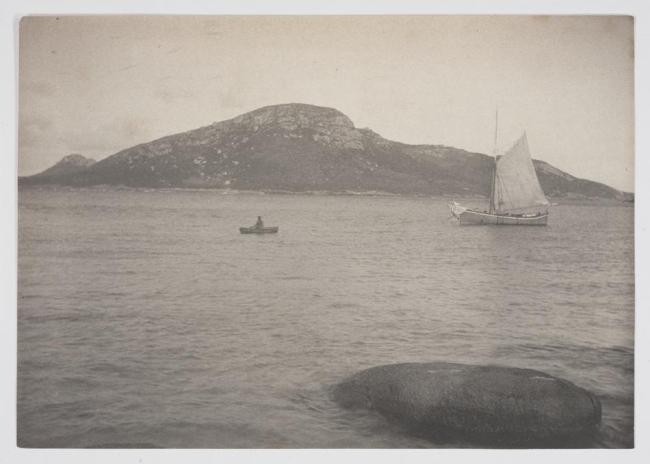

Boats of the kind built on Cape Barren, off Babel Island, 1893. Image courtesy of Museum Victoria.

Woorrady learned his skills in his home country – Bruny Island. He built canoes as he travelled throughout the south west and west coasts of Tasmania – travelling with Robinson in an effort to bring an end to the war between Aborigines and the invading British settlers. When Aborigines were removed by the Governor to the islands of Bass Strait, Woorrady continued to make canoes as he needed them.

Buck Brown continues this tradition as one of a small number of today’s Tasmanian Aboriginal Canoe Masters. Like the un-named young man who inspected Péron’s boat, like Mangerner and Woorrady, Buck comes from a family of master boat-builders. Since the late 1800s, Buck’s family has been building boats on Cape Barren Island – in the same waters that carried Woorrady’s watercraft. From sleek, fast cutters, to luggers and other fishing boats, Cape Barren boats have met the needs of the Aboriginal community up to the present day.

In 2014, the culture of Tasmanian Aboriginal boat building comes to MONA.

CLICK ON THE DATE TO GO TO SOURCE

ningher, the ‘catamaran’ – 1830

from the journals of George Augustus Robinson,

13 February, 1830 – Port Davey

Proceeded on towards the entrance of the first river at Port Davey on the eastern side 20 This river, the natives acquainted me, I had to cross. How to accomplish this was the question, as it was then blowing hard from the north-west and a heavy sea was rolling into the river. The natives informed me that I must cross in a catamaran. Ordered the men belonging to the escort party to make one, but they said they knew nothing about it. Requested the natives to make one…

Proceeded on towards the entrance of the first river at Port Davey on the eastern side 20 This river, the natives acquainted me, I had to cross. How to accomplish this was the question, as it was then blowing hard from the north-west and a heavy sea was rolling into the river. The natives informed me that I must cross in a catamaran. Ordered the men belonging to the escort party to make one, but they said they knew nothing about it. Requested the natives to make one…

15 February

Strong wind from the north-west. Natives finished the catamaran. Four of the men carried it on their shoulders, the distance of a mile. There it was launched and I proceeded across in it… being ebb tide the rest of the people forded the river higher up, but as the tide was flowing fast I was obliged to send the catamaran and a female aborigine for one of the people as it was out of his depth. These catamarans are ingeniously constructed of the bark of the tea-tree shrub and when properly made are perfectly safe and are able to brave a rough sea. They cannot sink from the buoyancy of the material and the way in which they are constructed prevents them from upsetting. The catamaran is made of pieces of bark… which when collected in a mass are tied together with long grass, called LEM.MEN.NE. The southern natives call the tea-tree NING.HER.

Strong wind from the north-west. Natives finished the catamaran. Four of the men carried it on their shoulders, the distance of a mile. There it was launched and I proceeded across in it… being ebb tide the rest of the people forded the river higher up, but as the tide was flowing fast I was obliged to send the catamaran and a female aborigine for one of the people as it was out of his depth. These catamarans are ingeniously constructed of the bark of the tea-tree shrub and when properly made are perfectly safe and are able to brave a rough sea. They cannot sink from the buoyancy of the material and the way in which they are constructed prevents them from upsetting. The catamaran is made of pieces of bark… which when collected in a mass are tied together with long grass, called LEM.MEN.NE. The southern natives call the tea-tree NING.HER.

What Makes Us

What makes Tasmanian Aborigines persist with the ‘Old Ways’? Language is spoken, and shell necklaces, kelp water carriers and grass baskets are made to practise our identity and culture.

One of the things that keeps our cultural practices alive is a deep knowing that the idea of modern progress is worth nothing unless it is balanced with the wisdom of tradition and the knowledge of culture. The First Nations of Tasmania were swept from their country in the name of development just two lifetimes ago. The past lives with us – makes us. Our families are the survivors of Tasmania’s Black War. This is who we are.

To breath life into the Old Ways is not just to re-claim them; it is to unleash our spirit upon the modern world – knowing that when we do this, we give life to our ancestors. They breathe with our lungs, and speak with our voice. They guide our hands.

When Brendan (Buck) Brown, Sheldon Thomas, Tony Burgess and Shayne Hughes created tuylini, the stringy bark canoe for the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in 2007, it was the first full-sized canoe made by Tasmanian Aboriginal hands since our people were exiled to Flinders Island in 1832.

Image courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Charles Alexandre Lesueur, 1778-1846.

Canoes like this were recorded by Nicholas Baudin’s expedition to Van Diemen’s Land in 1802. One of his artists sketched these canoes being used in Great Oyster Bay. There has not been a public exhibition of Tasmanian maritime technology in action since that time. In 2014, Dark Mofo changes all that.

We have called this project ningher – a word for ‘canoe’ recorded by both the French expeditions (neunga/nenga), and later English records. As ningher voyages from the site of its creation at MONA to Sullivan’s Cove, it will carry the makers to a place of ceremony that will be presented in palawa kani, the Tasmanian Aboriginal language of today. Ancestral stories, knowledge and spirit converge with contemporary language and culture. Tradition, survival, innovation. This is the richness of Tasmania’s deep history.

CLICK ON THE DATE TO GO TO SOURCE

ningher country

ningher comes out of country

wherever there is paperbark, reeds and water

ningher waits.

Without water they would not be made.

Culture that draws them out of the bush

always for a journey. Each unique.

Hands that shape, bend, tie.

ningher is formed from country

ningher is country.

Images courtesy of Greg Lehman

CLICK ON THE DATE TO GO TO SOURCE

The Flow of Culture

image courtesy of Monissa Whiteley

Where does it begin? Culture I mean. Somewhere in the past? Does it come from history? Is it made in the past and somehow handed on to us? We live in a world that is supposed to be passing us by – every minute – every second. Makes you feel a little desperate doesn’t it.

But what if this was all nonsense? What if the past and the present, and the future for that matter, all exist together. In a world like that, culture comes from a place called now. It is made of what we do – how we live our lives, what we believe and what has meaning for us. This is the place that ningher comes from. We call it Aboriginal Tasmania. It’s a place where the past is not dead and gone, but lives inside our hearts and minds – in our very DNA. When you walk on country with someone like Master Canoe-maker Brendon (Buck) Brown, or Community Artist Jamie Everett, you’re not looking for culture – you’re already in it.

Ask either one of them where their ability to master the complicated process of crafting a ningher (paperbark), or tuylini (stringybark) canoe according to the ancient traditions of their ancestors , and they are likely to stare deep into your eyes and bring their fist to their chest with the words “…from in here mate.” This is the Tasmanian Aboriginal culture of today.

Image courtesy of Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

Commencing on 20 June, 2014, the ningher voyage will be the first on Hobart’s famous River Derwent by Aboriginal canoe for over 180 years. Share the journey as Buck and Jamie commence the making of ningher – a paperbark canoe that brings the maritime technology and history of Tasmanian Aboriginal culture to the 2014 Dark Mofo Festival. From the gathering of raw materials from across the island, to the painstaking tie-ing together of bundles of bark and reed with hand made string, and finally the historic journey along the river from MONA to Waterman’s Dock in Sullivan’s Cove, you can be a part of this celebration of Tasmanian Aboriginal culture and story-telling. Keep an eye on this blog and our facebook page as the story unfolds.

20,000 Years of Tasmanian Boat Building [Australian Wooden Boat Festival 2017]

In what had to be the most moving ceremony of the MyState Australian Wooden Boat Festival 2017, a Tasmanian Aboriginal man paddled quietly into Sullivans Cove on the morning of the first day to open the festival and connect us all to a culture of wooden boat building that long pre-dates European arrival. As an island people, Tasmanian aborigines relied on watercraft for hunting, for transport and for ceremony. They made these boats with the materials to be found in the Tasmanian bush and a heritage of traditional skills and knowledge passed down through many generations. Traditional boat builder Sheldon Thomas collected the cork weed, bark and made the rope that lashed the craft together. Helped by members of his family and his community, he built a strong, stable, seaworthy craft of simple beauty that captured the attention of thousands of festival-goers.

Witnessed by scores of international visitors from the USA, the Netherlands, New Zealand as well as hundreds of Hobart families, the Tasmanian Aboriginal community did us the great honour of a moving welcome to their traditional lands. Carrying a smoking firestick to represent the cleansing of the festival site and moving to the haunting sound of Dewayne Everettsmith’s song in the language of his people, a procession of elders and family members entered Parliament House Lawns. Family elder Auntie Brenda spoke a heartfelt message of welcome and respect for all those who have gone before. Chairman Steve Knight accepted the firestick and was joined by Premier Will Hodgman, MyState MD Melos Sulicich and Dutch Deputy Ambassador Arthur den Hartog to mark the occasion.

‘I felt very much honoured by what Sheldon and his extended family did for us’, said general manager Paul Cullen. ‘We have huge respect for the long tradition of boat building that Sheldon has chosen to pass on and the knowledge that comes with it. These are no flimsy craft, these are beautiful canoes of strength and grace. Personally, I was fascinated to learn just a little about how they are made. There is not a piece of metal, adhesive, artificial binding or plastic in it. It is all made by hand from found materials and I have no doubt you could paddle it from here to Bruny Island and back again, as Sheldon’s ancestors would have done. This has great resonance for a festival of wooden boats; here is where the tradition started.’

No comments:

Post a Comment